I began this website because, as a lecturer on Surrealism and a private addict of freewriting, I was amazed that no one seemed to connect the two.

Surrealism comes from Freud, via Breton

The Surrealist movement was kicked off by the practice of automatic writing (art came later).

Surrealist automatic writing uses essentially the same method as modern-day freewriting in which you write continuously, allowing random processes to take over and suspending all critical judgment until the end of the exercise. [If you’d like more detailed instructions, please go to How to Freewrite].

André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement, used automatic writing as the basis to develop a whole philosophy of creativity which led to an entirely new approach to the practice of poetry, art and sculpture.

Breton himself had not come up with the idea of recording an unedited stream of consciousness. This, of course, was Sigmund Freud. Breton had used Freud’s method of free association when he was a medical orderly during the First World War and began to wonder if the unconscious could be harnessed in a similar was for the making of art.

Breton was enchanted with Freud’s ideas during the war when all things German were anathema. America, however, had adopted Freud early.

The Clark Lectures by Freud

In 1909, Freud gave a series of public lectures at Clark University in Massachusetts which were designed to reach a wide audience beyond professional, specialised psychiatric practitioners.

The Clark lectures are a good, basic introduction to Freud’s ideas about the unconscious, repression and the therapeutic work of psychoanalysis.

In the second of the lectures at Clark University, Freud likens a troubled patient to a lecture hall in which there is an audience member who is making a noise and interrupting the lecture. To regain calm and order, the troublemaker would have to be thrown out and guards would have to be placed on the doors to make sure he didn’t get back in.

In Freud’s analogy, the inside of the lecture hall is the conscious mind while outside the hall is the unconscious. And the man in the audience that is interrupting the lecture stands for an unacceptable thought that has to be ejected.

This is an illustration of repression: the trouble-maker who is ejected and prevented from getting back in represents an unacceptable thought repressed from the conscious mind. These unacceptable thoughts are, like the troublemaker in the lecture hall, disrupting civilised, social life, and must be thrust violently away, out of sight.

But Freud’s most important point was that the repression will continue to cause disruption.

In Freud’s illustration, the ejected man bangs on the door and generally continues to make his presence felt. In the same way, repressed thoughts, desires and emotions, continue to make the civilised, orderly lecture hall of the conscious mind a place of strife and discomfort. The problem of repression has not been solved.

The solution is to find someone who, like the psychoanalyst, can calm the trouble-maker enough so that he can be readmitted without causing any more disruption to the lecture. Hence the therapeutic work, involving dreams, free association and so forth will identify, and readmit the repression so that it can be put under the control of the conscious mind and tranquil, normal, life can resume.

Once the trouble-maker agrees to behave properly he can be re-admitted to the lecture hall. Civilised life goes on.

Surrealism is not therapeutic

You might assume that the Surrealists adopted automatic writing as an equivalent, therapeutic activity to Freud’s free association method, but you would be wrong!

The Surrealists wanted to unleash the revolutionary power of the unconscious and change society.

Breton and his group wanted to dismantle the institutions of public life such as the church and the government in order to claim the freedom of the individual.

You couldn’t get further away from Freud’s aims of re-integrating troubled individuals into civilised society!

Freud wants order; the surrealists want mayhem!

Freud’s example of the trouble-maker made ‘safe’ for the civilised lecture theatre has an equal and opposite counterpart in one of the most extreme statements Breton ever made. In the Second Surrealist Manifesto of 1929 Breton wrote:

The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.

Now, neither Breton nor any members of the Surrealist group in Paris or elsewhere were terrorists or mass murderers in real life, but this quote shows how far Surrealism is from the normalising aims of Freudian psychoanalysis.

You couldn’t get further away from Freud’s aims of re-integrating troubled individuals into civilised society.

Where Freud wanted to bring calm and individual peace of mind, the Surrealists were interested in finding extremes, nightmare and provocation.

Freewriting now

I find it fascinating that there is such a rich, hidden history to this common writing exercise which you can find recommended in almost any guide to creative writing.

Freewriting is also often recommended as a way to work on personal issues and problems and as a way to process difficult experiences. In this way, freewriting is being used as an equivalent to Freud’s free association method for therapeutic purposes and, like the treatment of Freud’s trouble-maker in the Clark lecture, the writer’s unconscious is safely corralled on the page and inner conflict defused.

But this is to completely erase the revolutionary aims of Surrealism, which is the ‘source’ of freewriting as an artistic technique.

For Breton and others of the group, the unconscious is a dark place, and artists and writers go there at their peril, even if sometimes what emerges is humour and irony. To take Surrealism to its extreme is to be profoundly at odds with every aspect of social life and inhabit a maladjusted state.

Why I Use Freewriting

My experience is that freewriting can produce work that is much stronger, stranger and more adventurous than anything I could create by slow, deliberate, rational and planned methods of writing. On a smaller scale to the Surrealism’s ambitions, freewriting has caused a revolution in my own life, causing me to literally leave the lecture halls of academia.

But at the same time, like Freud’s treatment of the noisy audience member, I find that releasing inhibitions in freewriting and then considering the results in a calm, constructive, way does seem to keep me on an even keel.

Freewriting has magical properties!

In being aware of the source of freewriting in Freud’s extraordinarily suggestive ideas or in the outrageous, liberating attitudes of the Surrealists, I believe we can find power and agency in our writing and lives through freewriting.

If you use freewriting, I’d love to know if you find that it promotes psychological well-being (a bit like DIY Freudian psychoanalysis).

I’d also love to know if you, like the Surrealists, have experienced it as a powerful and potent source of rebellion and creativity.

ncountered a film which, like Woolf’s stories and novels, throws away the hero’s journey and the linear plot. And I enjoyed it! It’s a French film called (in English) “Céline and Julie Go Boating”, from 1974. Unlike the Hollywood formula, this film has no familiar structure but works on repetition and improvisation, and it feels like a dream with surrealistic doubles and unclear chronology. But it’s funny, and enjoyable, and it really did draw me in so that I wanted to know what would happen in the end while accepting that I might not be given a resolution or a happy ending (in fact there IS a happy ending: a little girl is saved from being murdered, albeit in a parallel reality).

ncountered a film which, like Woolf’s stories and novels, throws away the hero’s journey and the linear plot. And I enjoyed it! It’s a French film called (in English) “Céline and Julie Go Boating”, from 1974. Unlike the Hollywood formula, this film has no familiar structure but works on repetition and improvisation, and it feels like a dream with surrealistic doubles and unclear chronology. But it’s funny, and enjoyable, and it really did draw me in so that I wanted to know what would happen in the end while accepting that I might not be given a resolution or a happy ending (in fact there IS a happy ending: a little girl is saved from being murdered, albeit in a parallel reality). on that have been borrowed, combined and re-fashioned in Wise Children (as indeed you could for the artists and writers in Swimming with Tigers).

on that have been borrowed, combined and re-fashioned in Wise Children (as indeed you could for the artists and writers in Swimming with Tigers).

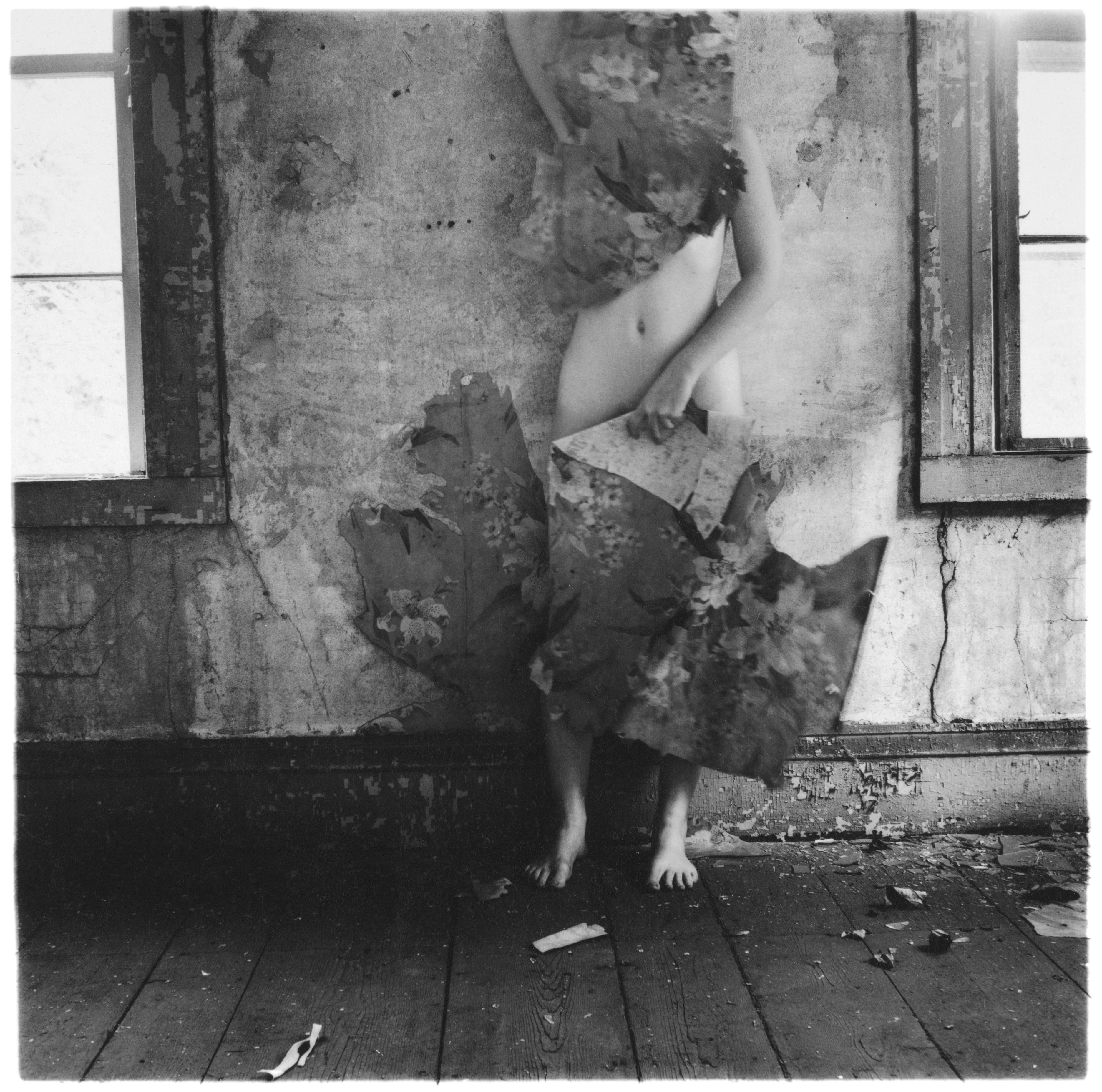

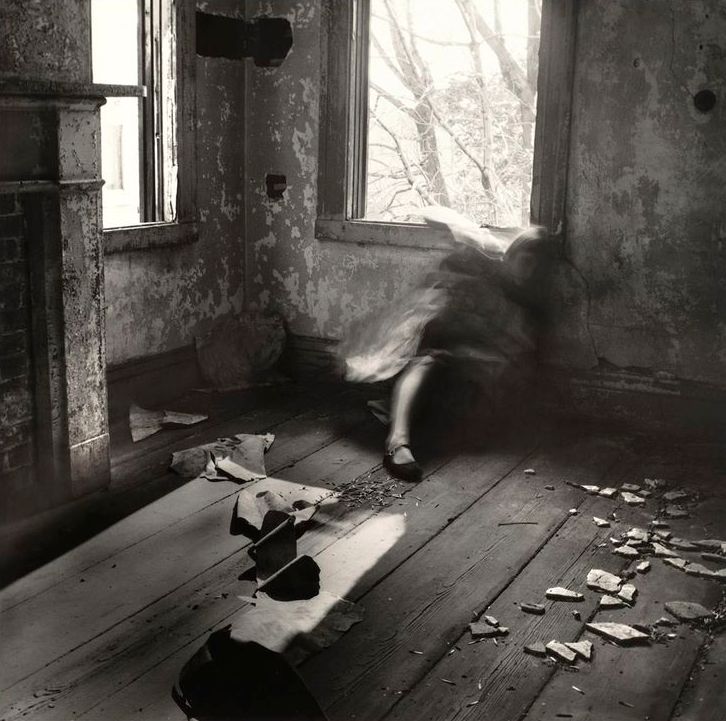

way it’s been set up and furnished, and the use of streaming natural light and blurring.

way it’s been set up and furnished, and the use of streaming natural light and blurring.

e eel representative of some phallic threat or promise next to her soft and undefended body? When I saw the picture in the exhibition it suggested to me the prospect of pregnancy: an uncanny portrayal of something curled up outside the body that might equally be furled inside. The beauty of the shapes and the textures, the lit edges of the uncanny fish and the homely bowl all contribute to make it a truly compelling image.

e eel representative of some phallic threat or promise next to her soft and undefended body? When I saw the picture in the exhibition it suggested to me the prospect of pregnancy: an uncanny portrayal of something curled up outside the body that might equally be furled inside. The beauty of the shapes and the textures, the lit edges of the uncanny fish and the homely bowl all contribute to make it a truly compelling image.