Francesca Woodman

Liverpool Tate’s summer exhibition is called Life in Motion and places paintings by Egon Schiele next to photographs by Francesca Woodman. Schiele was Austrian, working before World War One and Woodman was American, producing her photographs in the 1970s. Arguably the only thing that links them, apart from the predominance of self-portraits in their work, is the sad fact that both died in their early twenties. I went to the Tate solely to see the luminous, wonderful and unique work of Francesca Woodman who was influenced by Surrealism (and afterwards dutifully looked at the pitiless, misanthropic but technically brilliant work of Schiele). No surprise then that it’s Woodman’s work I’ll be describing here. I’ll be considering her as a woman photographer, an inheritor of Surrealism and in terms of the way she affects me as a viewer.

Woodman was working long after the “classic” period of Surrealism in the 1920 and 30s but was a devotee of Dada and Surrealism as a child, and later was particularly affected by the placement of the banal but suggestive documentary photographs included in Breton’s book Nadja. Her most obvious debt is to the many surrealist photographic techniques of long or double exposure, manipulation of light and many other methods designed to produce the strange and unsettling effects used by Man Ray for instance. But her strongest link with Surrealism is with a specifically female tradition of the self-portrait (often nude) which includes Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington and Léonor Fini among others. The amazing work of Claude Cahun who, in photographing herself, played with every aspect of her identity (most especially her gender) is surely Woodman’s direct artistic ancestor. These female surrealist predecessors are just as important as the 1970s context of feminist performance art by women such as Carole Schneeman which created the conditions for women to take themselves as the subject of their art.

Woodman was born in 1958 in Denver, Colorado to artistic parents and her ‘career’ as a photographer began at 13 years old. After high school she took an honours degree at Rhode Island School of Design, which included a year in Rome. She spent some time as an artist in residence in Peterborough, New Hampshire, and was living in New York at the time of her death. She was 22. In less than nine years, then, she achieved a body of work including between 500 to 800 pictures, of which 180 are in circulation as well as three books combining words and photographs and some video projects. Despite the fact that much of this was created when she was barely out of her teens, she has been described by Kris Somerville as “one of the most original artists of the 1970s and among the most influential photographers of the late twentieth century”. You might say she was a kind of Mozart of the camera.

Woodman’s first photo, taken at age 13, already has the signature style and basic ingredients of all her future work. It’s a self-portrait as the majority of her photographs are and her face is obscured as it often is, although here the effect of the hair covering her face is comical as well as mysterious. As Brian Dillon link says, it’s as though she’s channelling Cousin Itt from The Addams Family! The setting is characteristic too: a domestic interior made strange by the  way it’s been set up and furnished, and the use of streaming natural light and blurring.

way it’s been set up and furnished, and the use of streaming natural light and blurring.

Woodman’s main project, it seems to me, is to make herself strange to herself in as many ways as possible. She seeks to reconceive, extend, or de- or over-sexualise her body as a way of claiming it for herself. Her longest visual conversations are with domestic spaces which threaten to swallow her whole. She puts on old-fashioned clothes to pose questions about her role as a modern woman. She wears little-girl shoes to ask if she can be a child or to issue a riposte to their use by Hans Bellmer in his series of fetishistic schoolgirl doll photographs. For me, the repeated photographing of her own body gradually and thoroughly takes back the male-defined imagery of women as perverse object or anonymous muse found in Surrealist art.

Woodman’s pictures are staged and carefully composed. She is not really in disguise, like for example Cindy Sherman, who impersonates others such as the femme fatale film star, or characters in historical paintings. Sherman, who was born in 1954 and is still working, has spent her entire career making herself into other people. In contrast, although there is often a moment of uncertainty when viewing a Woodman self-portrait for the first time as you try to determine if it is indeed of the photographer herself, she is always recognisably the same person. But she repeatedly transforms herself.

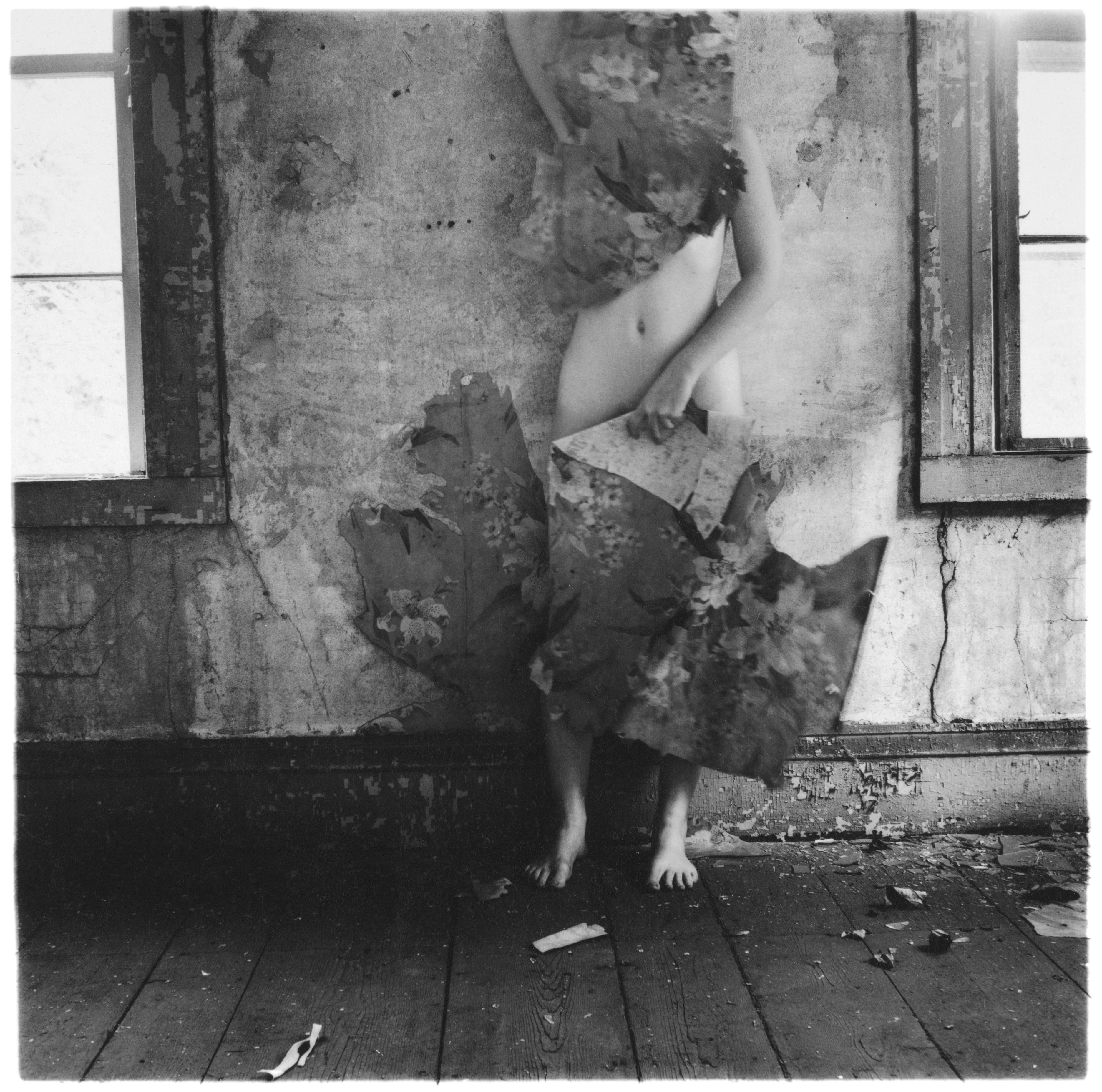

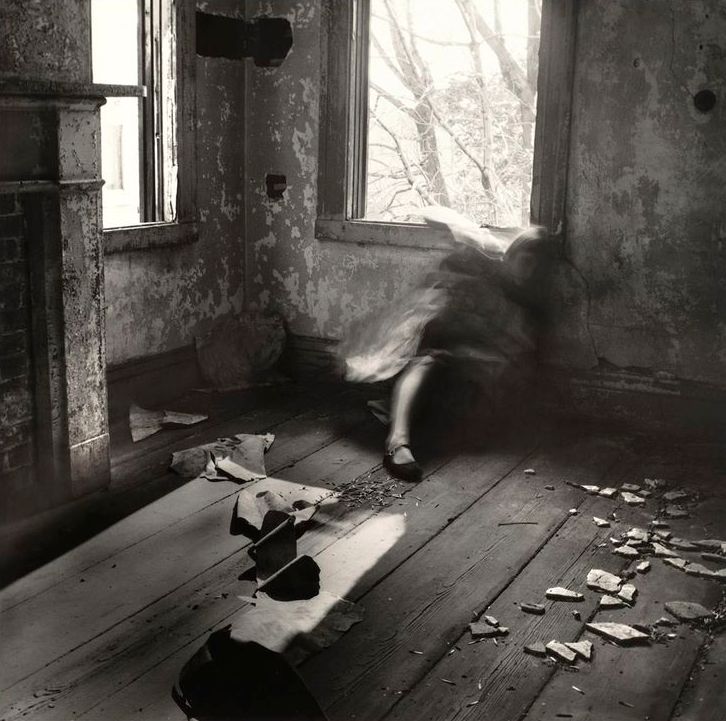

Often, it’s the physical environment that is the cause of the transformation as if to say that our identity is created by the spaces we inhabit. The third image from the series House (1976) presents a dilapidated room in a derelict house in clear focus but Woodman is, characteristically, swathed in a blur of light and wrapped in decaying matter. As in the other image from House I’ve included above, she is covered by wallpaper that has peeled off the walls, invoking Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s story of 1892 in which a confined woman goes mad and believes herself to be a part of the wallpaper of her prison. Woodman is arrested in motion, about to be engulfed in the long history of domestic confinement and the moment of dissolution seems to pose the question who is this? Is this me? It’s also strangely beautiful, a sort of dance with light and shape.

Another kind of questioning of identity is via the imitation of objects. One particularly haunting photograph shows Woodman posed next to a bowl containing an eel. It’s an endlessly ambiguous and fascinating image. Is th e eel representative of some phallic threat or promise next to her soft and undefended body? When I saw the picture in the exhibition it suggested to me the prospect of pregnancy: an uncanny portrayal of something curled up outside the body that might equally be furled inside. The beauty of the shapes and the textures, the lit edges of the uncanny fish and the homely bowl all contribute to make it a truly compelling image.

e eel representative of some phallic threat or promise next to her soft and undefended body? When I saw the picture in the exhibition it suggested to me the prospect of pregnancy: an uncanny portrayal of something curled up outside the body that might equally be furled inside. The beauty of the shapes and the textures, the lit edges of the uncanny fish and the homely bowl all contribute to make it a truly compelling image.

I realise that not all viewers at the Tate were as overwhelmed as I was, and that one reason might be the size of the photographs. They are mostly just 8 by 10 inches or even smaller. It means that viewing her work is a one-person activity since, as Jane Simon points out, there’s really only room for one viewer at a time. But this only increases the intimacy of the images. Although the photographs invite you to lean and peer closely, they are not at all voyeuristic, apart from the ones which consciously interrogate fetishism, and then the experience is intellectual rather than visceral, I found. Also, the square format she favours seems to hark back to Renaissance painting and it repeats the frequent setting of the room with straight lines forming a sort of hard cell for her supple, soft body.

There’s no doubt that Woodman’s photographs are partly about confinement but by turning her body into so many different things she becomes a series of metaphors (I am covered in bark, I am curled like an eel, I am a wall, a fireplace, a museum exhibit, etc etc). Woodman’s protean incarnations on celluloid proclaim are accomplished, generous, witty and feminine acts of transformation and in this way she moves towards freedom of identity and expression. Go see them!!

Like you, I am also a fan of Francesca Woodman and was over the moon to see a significant exhibition of her work in the UK. Whilst I don’t share your dislike of Schiele’s work (I’m actually a great admirer and appreciator of his) I did find it quite offensive that FW was clearly given second billing at this exhibition. The poster for instance showed Schiele work but nothing by Francesca Woodman, as if she were somehow playing second fiddle to a greater artist, which simply isn’t the case, and for this exhibition it could easily be argued that hers was the more interesting and representative half.

I would also say that, much as it was a huge pleasure to see genuine FW works in the flesh as it were, the premise of the exhibition (struggles with body identity) was a stretch at very best, and (in my view, in Francesca Woodman’s case at least) just plainly incorrect: a terrible case of the art intellectual trying to manufacture something from the flimsiest pretext with the flimsiest evidence.

However, enough of the griping – let’s get onto FW.

I believe that FW can best be understood primarily as a photographer discovering and exploring her medium rather than an artist being driven primarily by particular intellectual urges – I believe that when she is seen this way, it is more a reflection of the critic’s particular interests than from the totality of the evidence when exploring FW’s oeuvre.

From her earliest works, in the 2 to 3 years between her first recorded photograph and her entrance into the Rhode Island School of Design, we see her discovering all the magical transformations that black and white photography can bring to the world. From personal experience I can attest to what an addictive process this can be, especially during formative years for someone with an unfettered imagination, and I see FW discovering such wonders (its ability to either stop or blur time; depth of field/depth of focus; how light transforms as it falls in different ways; pattern; texture; the ability to suggest stories and iconographies through staged images; the exploration of self) in this initial period. I believe it is also important to remember that the vast majority of her most memorable and brilliant images were created in the frame of a taught course in photography.

We must remember that, although it was her father who gave her her first camera (a Yashica 6×6 twin lens reflex, which dictated the square format of much of her best work), it was an art teacher at Abbott Academy Boarding School, Wendy Snyder MacNeill, who first properly encourgaed and guided her interest.

Her parents then further encouraged her blossoming interest and talent by sending her RISD in 1975, from where she graduated in 1979, thus all of the work in this period must be seen in the context of taught course work, as well as part of the particular and unique vision of Francesca Woodman herself.

Black and White film photography is taught in a particular (and to a large extent, necessary) way in order give the practitioner the required control over the medium. Thus students are given assignments in (for instance) high key (images consisting of mostly white or light tones) versus low key (shadow or dark tones) in order to learn how to control light and shadow in the negative and then in the print. The next lesson will then be in how to achieve and control full tonal range images (succesfully handling a full contrast image to reproduce the deepest blacks and the lightest of highlight details in the same negative). We can see FW exploring all of this in her Rhode Island and Italian images. We see her experimenting with the ‘active frame’ (having the main subject only partly in/out of the image, thus forcing the viewer to imagine the rest), with formal versus skewed frames (a properly squared off image with straight and parallel lines gives a very formal and organised feel, while deliberately skewed verticals/horizontals/parallels introduces a subliminal sense of tension (see the work of Garry Winogrand). We also see her discovering the power of sequencing; of how a number of images next to each other creates a ‘cinema of stills’ where the sum of the images is much greater than the individual photographs themselves (see the work of Minor White). All of these things would have been part of any taught photography course at the time (and I must try and hunt down the RISD course content for the time).

However, in addition to this overall framework, we also see FW’s own interests emerging, the things that made her unique as an artist, and again, if you look at her whole body of work rather than just her most frequently reproduced images, I believe that we find, rather than an oeuvre driven by particular political or intellectual impulses, an exploration of multiple and ever changing themes, but always driven by the visual impact of the final planned image (and yes, from her notebooks we know that she planned many of her images in minute detail, as any determined and ambitious student would do).

So although she was undoubtedly intersted in clothes, fashion, personal identity, surrealism, futurism etc. I believe that that these were all secondary to her drive to explore the medium in her own particular way.

It also seems clear that she saw the photographic frame as a stage set in which she could’t help being director, producer, and of course, more often than not, also the central character. From all accounts of her by her friends it would seem unfair and innacurate to label her as narcissistic, but she most certainly loved to create drama (see Sloane Rankin’s description of their first meeting in the documentary ‘The Woodmans”, or the deliberatley affected “Steinwriting” style of her journals) and was constantly exploring and playing with her own personality and identity. Her insistence, when asked about why she was the subject in so many of her own images that “It’s a matter of convenience, I’m always available” seems slightly disingenous – not only was she truly interested in her own identity and all of the many characters that she could become, but also, she couldn’t helped but notice that the vast majority of her best works were of herself. For a highly ambitious photographer (and everyone who knew her agreed that ambition was a huge driver in her life), why not stick to your most succesful subject matter.

She also appeared to me to gravitate towards icons, again simply because they made the most powerful images. We can see for instance in the 2006 Phaidon eponymous publication of her work, how her famous “eel” photographs didn’t emerge out of nowhere. Even in some of her earliest works pre-RISD we see her using strops ans straps to produce these sensuous shapes, then at RISD, a snake moving over her body, then finally in Rome as part of the RISD European Exchange Programme, she visits the local market, simply to buy interesting objects (fish, fruit etc.) to photograph, and eventually, the most succesful combination turns out to be FW + bowl + eel! Likewise we see that her famous Angel Series is part of an exploration throughout her work of the images of wings (dead birds, her own arms etc.) Icons in art (just as in the rest of life) shouldn’t be seen necessarily in terms of a person latching onto or copying already existing themes, but perhaps more usefully in terms of parallel eveolution i.e. the same themes emerge again in again, in biological terms because they are the most succesful and practical, and in artistic terms because they are the most compelling and seem to reflect themes deeply embedded in human nature in general.

There are so many other strands that could be explored in the work of Francesca Woodman, but this exhibition certainly lead me to try and research her in a little more depth and try understand her life in a little more detail and try to discover what seemed to drive her.

In this vein, I’d strongly recommend ‘The Woodmans’ documentary and 3 excellent books which span a good range of her images (plus a variety of essays and commentaries): Francesca Woodman – Phaidon 2006; Francesca Woodman – Fondation Cartier pour l’arte contemporain 1998 and ; Francesca Woodman – San Francisco Museum of Modern Art 2011.

Apologies for the inevitable grammatical errors and spelling mistakes which will have slipped in – hopefully the content will stimulate some further discussion!

Thanks, Rich, for this long and considered comment: you should have a photography blog of your own (although you might have to give up the dayjob to find time for it…).

I absolutely agree that we should beware of critics’ interpretations and that one influence, such as surrealism, can’t hope to “explain” her work. But my question to you is this: could Francesca Woodman have produced these images at this time WITHOUT being familiar with surrealist photography and ideas? And without the strong line of women surrealist artists and photographers (Frida Kahlo and Claude Cahun for instance, who were just coming into popular view, or Lee Miller, and so on) would she have had the “permission” to take herself as her chief subject?

To me, she seems to treat her body in the same way in which she approaches the objects and environments that, as you say, captivate her as technical exercises or challenges and this way of seeing the female form is highly unusual, non-voyeuristic and intensely valuable. It’s also something that I don’t think could have been done without the burgeoning feminist art movement, inspired in part by the rediscovery of women surrealists.

But of course the beauty of really good (great?) art is that it speaks to all of us, and in different ways. I loved reading about the details of photography training, and seeing Woodman through your (photographer’s) eyes.